Recently a very strange result has been making the rounds. It says that when you add up all the natural numbers

1+2+3+4+...

then the answer to this sum is -1/12. The idea featured in a Numberphile video (see below), which claims to prove the result and also says that it's used all over the place in physics. People found the idea so astounding that it even made it into the New York Times. So what does this all mean?

The Maths

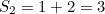

First of all, the infinite sum of all the natural number is not equal to -1/12. You can easily convince yourself of this by tapping into your calculator the partial sums

and so on. The  get larger and larger the larger

get larger and larger the larger  gets, that is, the more natural numbers you include. In fact, you can make

gets, that is, the more natural numbers you include. In fact, you can make  as large as you like by choosing

as large as you like by choosing  large enough. For example, for

large enough. For example, for  you get

you get

get larger and larger the larger

get larger and larger the larger  gets, that is, the more natural numbers you include. In fact, you can make

gets, that is, the more natural numbers you include. In fact, you can make  as large as you like by choosing

as large as you like by choosing  large enough. For example, for

large enough. For example, for  you get

you get![\[ S_ n = 500,500, \]](https://plus.maths.org/MI/df22fe35c1987e39a64d7f0ffa2d3e51/images/img-0010.png) |

and for  you get

you get

you get

you get![\[ S_ n = 5,000,050,000. \]](https://plus.maths.org/MI/df22fe35c1987e39a64d7f0ffa2d3e51/images/img-0012.png) |

This is why mathematicians say that the sum

![\[ 1+2+3+4+ ... \]](https://plus.maths.org/MI/b48eec2db5d26f324e8213f2b232e449/images/img-0001.png) |

diverges to infinity. Or, to put it more loosely, that the sum is equal to infinity.

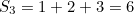

Srinivasa Ramanujan

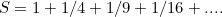

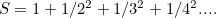

So where does the -1/12 come from? The wrong result actually appeared in the work of the famous Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan in 1913 (see this article for more information). But Ramanujan knew what he was doing and had a reason for writing it down. He had been working on what is called the Euler zeta function. To understand what that is, first consider the infinite sum

You might recognise this as the sum you get when you take each natural number, square it, and then take the reciprocal:

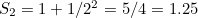

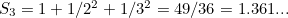

Now this sum does not diverge. If you take the sequence of partial sums as we did above,

then the results you get get arbitrarily close, without ever exceeding, the number  Mathematicians say the sum converges to

Mathematicians say the sum converges to  , or more loosely, that it equals

, or more loosely, that it equals

Mathematicians say the sum converges to

Mathematicians say the sum converges to  , or more loosely, that it equals

, or more loosely, that it equals

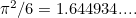

Now what happens when instead of raising those natural numbers in the denominator to the power of 2, you raise it to some other power  ? It turns out that the corresponding sum

? It turns out that the corresponding sum

? It turns out that the corresponding sum

? It turns out that the corresponding sum![\[ S(x) = 1+1/2^ x+1/3^ x+1/4^ x... \]](https://plus.maths.org/MI/43dead62fc5884aa61fb4f438394aa46/images/img-0012.png) |

converges to a finite value as long as the power  is a number greater than

is a number greater than  . For every

. For every  , the expression

, the expression  has a well-defined, finite value.

has a well-defined, finite value.  is what’s called a function, and it’s called the Euler zeta function after the prolific 18th century mathematician Leonhard Euler.

is what’s called a function, and it’s called the Euler zeta function after the prolific 18th century mathematician Leonhard Euler.

is a number greater than

is a number greater than  . For every

. For every  , the expression

, the expression  has a well-defined, finite value.

has a well-defined, finite value.  is what’s called a function, and it’s called the Euler zeta function after the prolific 18th century mathematician Leonhard Euler.

is what’s called a function, and it’s called the Euler zeta function after the prolific 18th century mathematician Leonhard Euler.

So far, so good. But what happens when you plug in a value of  that is less than 1? For example, what if you plug in

that is less than 1? For example, what if you plug in  ? Let’s see.

? Let’s see.

that is less than 1? For example, what if you plug in

that is less than 1? For example, what if you plug in  ? Let’s see.

? Let’s see.![\[ S(-1) = 1+1/2^{-1}+1/3^{-1}+1/4^{-1}... \]](https://plus.maths.org/MI/2b5df501aae647079e305b7f698f8180/images/img-0003.png) |

![\[ = 1+2+3+4+ ... . \]](https://plus.maths.org/MI/2b5df501aae647079e305b7f698f8180/images/img-0004.png) |

So you recover our original sum, which, as we know, diverges. The same is true for any other values of  less than or equal to 1: the sum diverges.

less than or equal to 1: the sum diverges.

less than or equal to 1: the sum diverges.

less than or equal to 1: the sum diverges.Extending the Euler zeta function

As it stands the Euler zeta function S(x) is defined for real numbers x that are greater than 1. The real numbers are part of a larger family of numbers called the complex numbers. And while the real numbers correspond to all the points along an infinitely long line, the complex numbers correspond to all the points on a plane, containing the real number line. That plane is called the complex plane. Just as you can define functions that take real numbers as input you can define functions that take complex numbers as input.

One amazing thing about functions of complex numbers is that if you know the function sufficiently well for some set of inputs, then (up to some technical details) you can know the value of the function everywhere else on the complex plane. This method of extending the definition of a function is known as analytic continuation. The Euler zeta function is defined for real numbers greater than 1. Since real numbers are also complex numbers, we can regard it as a complex function and then apply analytic continuation to get a new function, defined on the whole plane but agreeing with the Euler zeta function for real numbers greater than 1. That's the Riemann zeta function.

But there is also another thing you can do. Using some high-powered mathematics (known as complex analysis, see the box) there is a way of extending the definition of the Euler zeta function to numbers  less than or equal to 1 in a way that gives you finite values. In other words, there is a way of defining a new function, call it

less than or equal to 1 in a way that gives you finite values. In other words, there is a way of defining a new function, call it  so that for

so that for

less than or equal to 1 in a way that gives you finite values. In other words, there is a way of defining a new function, call it

less than or equal to 1 in a way that gives you finite values. In other words, there is a way of defining a new function, call it  so that for

so that for

and for  the function

the function  has well-defined, finite values. This method of extension is called analytic continuation and the new function you get is called the Riemann zeta function, after the 19th cenury mathematician Bernhard Riemann. (Making this new function give you finite values for

has well-defined, finite values. This method of extension is called analytic continuation and the new function you get is called the Riemann zeta function, after the 19th cenury mathematician Bernhard Riemann. (Making this new function give you finite values for  involves cleverly subtracting another divergent sum, so that the infinity from the first divergent sum minus the infinity from the second divergent sum gives you something finite.)

involves cleverly subtracting another divergent sum, so that the infinity from the first divergent sum minus the infinity from the second divergent sum gives you something finite.)

the function

the function  has well-defined, finite values. This method of extension is called analytic continuation and the new function you get is called the Riemann zeta function, after the 19th cenury mathematician Bernhard Riemann. (Making this new function give you finite values for

has well-defined, finite values. This method of extension is called analytic continuation and the new function you get is called the Riemann zeta function, after the 19th cenury mathematician Bernhard Riemann. (Making this new function give you finite values for  involves cleverly subtracting another divergent sum, so that the infinity from the first divergent sum minus the infinity from the second divergent sum gives you something finite.)

involves cleverly subtracting another divergent sum, so that the infinity from the first divergent sum minus the infinity from the second divergent sum gives you something finite.)

OK. So now we have a function  that agrees with Euler’s zeta function

that agrees with Euler’s zeta function  when you plug in values

when you plug in values  . When you plug in values

. When you plug in values  , the zeta function gives you a finite output. What value do you get when you plug

, the zeta function gives you a finite output. What value do you get when you plug  into the zeta function? You’ve guessed it:

into the zeta function? You’ve guessed it:

that agrees with Euler’s zeta function

that agrees with Euler’s zeta function  when you plug in values

when you plug in values  . When you plug in values

. When you plug in values  , the zeta function gives you a finite output. What value do you get when you plug

, the zeta function gives you a finite output. What value do you get when you plug  into the zeta function? You’ve guessed it:

into the zeta function? You’ve guessed it:![\[ \zeta (-1)=-1/12. \]](https://plus.maths.org/MI/cbd4ca0ab047fec3f3b541a4f94b4c17/images/img-0012.png) |

If you now make the mistake of believing that  for

for  , then you get the (wrong) expression

, then you get the (wrong) expression

for

for  , then you get the (wrong) expression

, then you get the (wrong) expression![\[ S(-1) = 1+2+3+4+ ... = \zeta (-1) = -1/12. \]](https://plus.maths.org/MI/cbd4ca0ab047fec3f3b541a4f94b4c17/images/img-0014.png) |

This is one way of making sense of Ramanujan’s mysterious expression.

HOPE THIS WILL HELP YOU!!!

ReplyDelete